In the studio with Paul Bong

In the lead up to print maker Paul Bong’s upcoming exhibition Error of Parallax, FireWorks Gallery Director, Michael Eather, visited Paul in his Innisfail studio and discussed his new works, his artistic approach to printmaking and the new imagery of Captain Cook.

ME: This new body of work has a lot of the old etching plates coming through but introducing new elements. Tell us how you start thinking like this. What goes through your head when you are in the studio working like this?

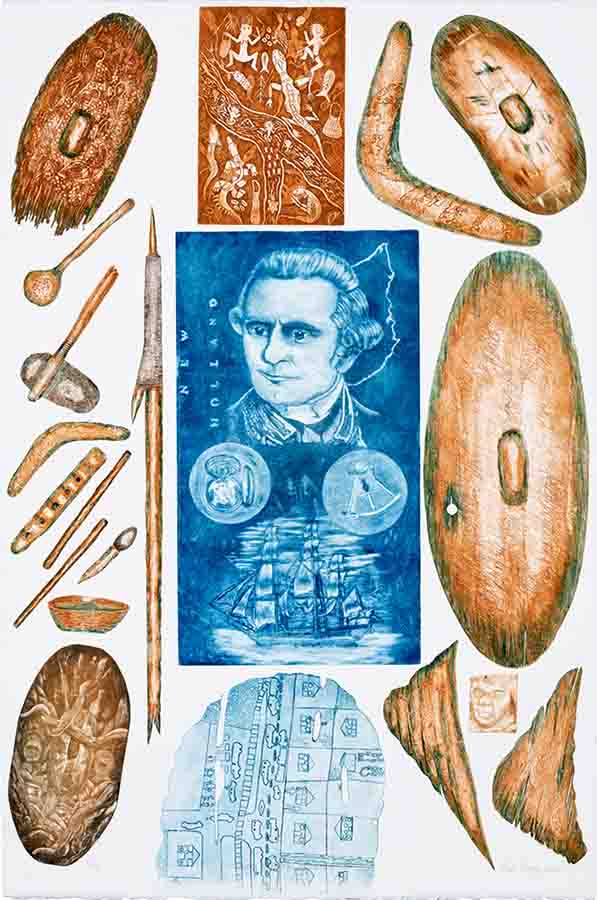

PB: Sometimes you look at your old pieces and think, “How can I better it?”. As an artist you have to keep looking. I like to try different things. And that’s why, in the new pieces, I thought, I’ve got enough etching plates with what I’ve done over the years, with dispersed fragments through to political artwork and stuff like that. And I thought well, I can put all those pieces together and make an art piece out of it in an abstract look. In my art I haven’t previously explored, though I’ve always loved, abstract. It has always been in the back of my mind. I started off just doing one plate and then talking about that one plate and putting our culture together with the political statements. This time I’m going to mix and match. I thought I would just do a couple at first to see what it looked like. I started with the small pieces, with really bright colours coming through and then I thought to myself, “Wow, this really looks different”. And then I started to work on big pieces and use techniques like collagraph, and collage and putting the etching in and working with lino and all these different see-through images on top of each other, so it’s transparent, you can see the bottom.

PB: Sometimes you look at your old pieces and think, “How can I better it?”. As an artist you have to keep looking. I like to try different things. And that’s why, in the new pieces, I thought, I’ve got enough etching plates with what I’ve done over the years, with dispersed fragments through to political artwork and stuff like that. And I thought well, I can put all those pieces together and make an art piece out of it in an abstract look. In my art I haven’t previously explored, though I’ve always loved, abstract. It has always been in the back of my mind. I started off just doing one plate and then talking about that one plate and putting our culture together with the political statements. This time I’m going to mix and match. I thought I would just do a couple at first to see what it looked like. I started with the small pieces, with really bright colours coming through and then I thought to myself, “Wow, this really looks different”. And then I started to work on big pieces and use techniques like collagraph, and collage and putting the etching in and working with lino and all these different see-through images on top of each other, so it’s transparent, you can see the bottom.

ME: Do you think more like a sculptor than a printmaker?

PB: I’m pretty sure I am. I like to muck around with sculpture. When you look at printmaking it is sculpture, it is sculpting but on a flat plate and therefore you are doing your sculptures with acid and you’re using different timings. You don’t know how it’s going to come out but you’re chipping away. You’re chipping away the words with the acid that’s creating all the different textures on your plate and then when you print it you can go over it and whatever you don’t like, things coming out too dark, or maybe not enough, you can sculpt it again, you can get into it and scratch, you can burnish it and bring it back. Whereas probably in the sculpture form, say with wood or cement, you have to get it right first whereas [printmaking] allows you to play around, you can get it darker again, you can get it lighter again.

ME: Tell me, with the etching plates themselves, they are like pieces of sculpture that you’ve made and you reuse them differently in different times. Tell us also about how you started getting interested in the plates as fragments and the “murrifactive” stamp you made a few years ago.

ME: Tell me, with the etching plates themselves, they are like pieces of sculpture that you’ve made and you reuse them differently in different times. Tell us also about how you started getting interested in the plates as fragments and the “murrifactive” stamp you made a few years ago.

PB: At that time I worked with a bloke called Theo Tremblay and I was his apprentice. I was working with a technique that no one else was working with. And as I printed the pieces out, then I started to get more political and he made up a stamp. We used it as a museum accession stamp.

This time, it’s just a thought in my head, that I’ll probably use a barcode maybe, whether to use a real barcode or do my own pretend barcode and let the people know, why is that little thing there, because it was made to make an old object come to life again, like you’re unearthing something that’s right in front of your face. Whereas I know that most of our stuff is in the museums and farmers probably holding onto them, so the only way that I can do it is to do it through etching plates.

ME: You’re talking about history. And with your fascination with history you have introduced good old Captain Cook. I’m nicely surprised to hear you talk about him in such an even way. Tell us about your thoughts on those older days?

PB: Cook, when he came over, you know I believe, this is just me, people out there can believe whatever they want to believe, but this is what I have read of him. He was a man that was probably looking for fame back in the days and then he came across a country and he didn’t know what was here really. He came to Sydney, he met a couple of Aboriginal people there and stuff happened there and then he came up along the coast, right up to Cairns and Cooktown where we are from. Cook had another bloke, a botanist, Banks, they both travelled together and one was looking for plants and he was looking for history.

ME: So you see Cook as a reasonable fellow?

PB: Yeah, because I don’t believe he did anything wrong. If any other people came across, like from another country, there was a lot of other people ready to explore and overtake different countries, it could have been French. I believe Cook, he never done the massacre. He only did the [founding/finding] of Australia and he went back and he told the Queen. The ones that came after him are the ones that did the bad things. So that’s what I believe.

ME: And you’re actively trying to remind people, through your art, of that history aren’t you?

ME: And you’re actively trying to remind people, through your art, of that history aren’t you?

PB: I’m trying to remind people of the history and trying to tell them that he wasn’t a bad bloke. The reason why I often put him into my projects is because if you look at his hair style and you look at his dress that represents the government. And everybody knows Cook, I’m using his face as a governmental symbol. I’m saying the government came over here with their law, the government massacred us, the police force – which all still comes under the government, the courthouse, it all still comes under the government, the way he wore his wig, that’s representing the government. That’s why I use his face in my pictures a lot, because it represents the government that we are under.

ME: What about the Prussian blue?

PB: Prussian blue is a colour I know from back in the days. When I was a young kid I used to play with biros, it was a Prussian blue biro. And blue and red is the governments colours. Red came out later on as  I grew up, but blue was always there. And I love blue because if you put it into the right place it can form depth for you and that’s why I love Prussian blue, and you can mix Prussian blue with any colour and it will mix, it will make something dimensional.

I grew up, but blue was always there. And I love blue because if you put it into the right place it can form depth for you and that’s why I love Prussian blue, and you can mix Prussian blue with any colour and it will mix, it will make something dimensional.

ME: When you mentioned the word abstract before, do you mean abstract in the layering sense, putting layers upon layers? Is abstract something that doesn’t necessarily make visual sense at once, it’s a combination of things?

PB: If you look at the old cave art and how they did a figure, you can see it’s a man but it’s not photographic, it’s an image. You can see the head, you can see the body and then behind it you can see, say a lizard, and then the lizards sort of wear-out, but it’s there. It’s this fragmented sort of thing. And it’s abstract. That’s why I think I like abstract, because I can use my plates, putting it on top of each other and saying I want this piece in, but I don’t want this piece in. And then when you stand back and look at it, it’s telling a story but you’ve got to really tell the story to let the people know what you are doing. That’s why I like abstract, it’s a crazy art.

ME: You’re very driven here, you work in your studio pretty much every day, constantly starting new prints and revisiting old prints. What’s your message, what’s your greatest hope, what would you like your art to achieve for you?

PB: In my mind I would like to become one of the greatest artists, see I said one of… probably one of the greatest in the world. Every artist would probably like to do that, become famous. Plus, while I’m alive I would like to live off my earnings. They say fame doesn’t always come with money, fame is just something on its own, probably the dollars will come when you’re dead [laughs] – but I’m hoping not to look at it that way.

ME: How long have you been working in this capacity as a self-driven artist? Running your own enterprise?

PB: I’ve been here about 5-6 years. I’m trying to be a businessman and trying to be an artist and all these other things and trying to put them all together and trying to be a successful businessman-artist is really hard. I think you either have to be one or the other. But I’m going to just keep working until it all fits together. And sometimes it might not seem like the right thing, but it will happen. I believe it will happen. A lot of people said you’ll make your money but it doesn’t make too much difference to me. Like if I do, I do and if I don’t, I don’t. I’m used to it. If I don’t have no money here, I’m used to going down the creek and going fishing. I can live off the land. It’s no worries to me. Whereas most other people, they freak out, they commit suicide or if I gotta do without a car, it don’t worry me, I just keep walking around.

ME: With the show we had with you a few years ago, amongst many of the other works, the shield designs, and the bullet holes and the fragmentation, was the series Memories of Oblivion. This is where you introduced the whole chain of history from before contact and had the Union Jack coming in and bringing conflict with it. Tell us about that and how you are still using those ideas in your new work.

PB: I always wanted to do that series… I’m always stuck for a title, and I thought – I have to try really hard naming this piece because it goes from 50,000 years and ends up with the flag, the Union Jack, going right around. Except I left one piece untouched at the end, and that piece represents us and that we are still fighting and they didn’t take everything yet, that we are still fighting for what we got now.

With that series I couldn’t think of a title, so I took a photo of it. I knew a bloke from The Australian Times and he put Aboriginal artwork in there. I sent him an email and said, “Can you title this for me” and he sent back the word “Oblivion”, so I went and looked that up and thought, “Wow that’s a good word” so I ended up using that word.

ME: But you always give it [words] your own spin Paul. You make it your own. Take bits from here and there, a bit like your prints.

PB: Because I don’t know English that well, I been very bad schooling person, even at school I didn’t even know how to spell. That’s why I left in grade 7 to start work.

ME: Where did you work?

PB: My first job was here in Innisfail, at Pigeon Box Hill. I stared picking up stones in the early days, clearing the paddocks for farmers and stuff like that and then I ended up cutting cane and planting. Later on, I ended up getting married and having my own family and then I ended up going to college to get a [Associate] Diploma of Indigenous Art Studies at the age of 30. And even then, they probably couldn’t keep me in class because I like to walk around and do things. They would say, “Where are you going now?” and I would say, “I’m just going to the toilet” but I would be in the printmaking room and I kept going back to the printmaking room. They couldn’t keep me away from the printmaking room. And that’s where it started, I love printing.

When I name things now, I can rely on other people, and ask them what they think about it. Sometimes I use their words and sometimes I’ll find my own words. Purloin, that’s a flash way of saying stolen. And when I talk to people about purloin and when I’m there talking about my art, they’ll correct me on my pronunciation and say, it’s meaning this, you get the really English people…….

Most of my works, I do it in my head, I explain to the people what I’m doing, and most of it is titled by other people. I say if I like it. If not, I’ll go for a walk with a dictionary and I’ll just check it out and I’ll keep thinking on it. Now we’ve got Youtube, we can say to the Youtube, “What’s the meaning of this word?’ and you go through and you check all the words out and see if it does match what you’re doing in your head. So that’s how I do all my stuff hey. And I just tried to go that way.

ME: With the history, going back, you’ve lived some of that history. I remember you telling me stories of your grandmother too. Bringing that oral history together, which you have carried preciously in your mind of the old days. Tell us about your links to a time that is probably a treasure for you in the Aboriginal memory.

PB: Even now I sit down and talk to people about some things you remember as a child. Like my Granny, we called her Granny Sissy or Old Lady Sissy Bong Maratta, she was a lovely old lady from what I remember. I probably would have only been about ten or nine, and she used to take us down the creeks and do different things. I can think back on those things, catching prawns and running over snakes.

ME: Where was she from, your grandmother?

PB: She was from the Yidinji tribe in Gordonvale. I finally found her birth certificate, they had one for her, and she was born in the Gordonvale area and up in the Goldsborough. She wandered all around in those days. She was a full blood, on her birth certificate it said, not Gordonvale, it said a name before Gordonvale ever was Gordonvale. It was way back in the early days, she would have been seeing all the massacres and stuff like that.

ME: So she lived through some of those massacres, her parents or she saw them, she was a witness?

PB: Oh yeah, even her brother was stolen from her and that. But she always said to us, “You go the white man way because that’s a better way now”. In other words, she was trying to say, don’t fight them you’ll get killed anyway. She told my big brother that and my big brother ended up telling me. My oldest brother was about ten years older than me. When I was back in the early days, we grew up that way, the traditional ways because we were poor. And that’s the way we did things, learning through her and my grandfather, and language, we sort of knew a little bit of language, and story-telling. She told a lot of stories, mainly the traditional stories, it wasn’t the bad stories of being through it. She just said her brother been stolen, the white man came along and stole her brother and she didn’t see him till 70 years later, when he mentioned her traditional name and they both met at Edmonton. He mentioned her traditional name and they just both cried together and cried in the Aboriginal way of sitting down, mourning and crying and crying. It’s really eerie when you hear the story... She would hit herself and whack herself, they didn’t care if blood come out, that’s the way they mourn. They sat down and cried, all night for about two weeks. And my dad used to say, “just leave her go”. And she was in the same house as us and that’s all we can hear going to sleep, her mourning. That was sort of strange, but when I grew up, I grew my own way. What I was taught at school, I was taught that the farmers own all our land and that’s where I thought it was at. Until one day, I was down in Brisbane, and I met a white mate of mine, we used to go drinking a lot with all the other mates of ours, that’s who I used to get around with, I call them migaloos, white fellas, and we went to his place and his mother started talking to me about Aboriginal stuff and I didn’t really know too much about it. She said, “If I was you, I would go back home and I would learn about my culture, because you have the most beautiful culture and you don’t know too much about it”. From all the things that Granny had told me that I had forgotten about. So I came back home when I was about 20. I went back to all the old people and started talking to them. And that’s where it’s coming from, through that old lady down there, that old white lady from Brisbane and she told me to go back and learn about my culture and I’m lucky I listened to her. Six months later I was back home here, and I spent another 20 years here just to learn my culture and through to my art.

ME: Thank you for sharing. Anything else to mention?

PB: Only thing now is just to show the people all the stuff that’s running through my head and hope they enjoy it. If I’m not here to explain I hope they enjoy it and have a good understanding of who I am.

Paul Bong in conversation with Michael Eather, Innisfail studio, 30 May 2021

Images (in order reflecting the above sequence of images):

Image 1: Paul Bong Brought the religion in and disposed our culture ed. 1/5 2021 hand coloured intaglio etching on 300gsm paper 122x80cm FW20317

Image 2: Paul Bong Murrifactive stamp 2016

Image 3: Paul Bong The day we were invaded 2021 unique hand coloured intaglio etching & mixed media on 300gsm paper 120x80cm FW20369

Image 4: Paul Bong in his Studio 2021

Image 5: Paul Bong Memories of Oblivion Suite I-V (unframed) 2016 hand coloured intaglio etching 120x350cm FW17074

Images courtesy of the artist, FireWorks Gallery & Mick Richards