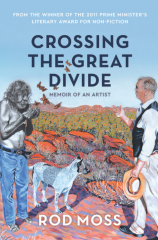

Crossing the Great Divide

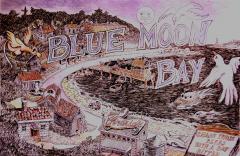

Blue Moon Bay

CROSSING THE GREAT DIVIDE

A Shared Humanity

John Anderson

The work of Rod Moss, based on his life in Alice Springs, spans a period from the mid 1980s through to today and is a remarkable record of the artist’s experience of life and family in that community and its surrounds. He would include in that family not only his own kin but also the broader community of aboriginal friends who have been so important to him during those years.

Enlivened and challenged by the traditional lifestyle and the urbanisation of the Arrernte families, Moss has devised a method of combining painting and drawing which depicts the realities of a life lived, coupled with a symbolic and heroic narrative. Through this he intensifies the drama of a cultural synthesis unique to the Alice, which as a settlement can be compared to a raft in a limitless sea. The Aboriginal elder Arrenye Pengarte Jonson’s intimate friensdship with Rod opened the spirit of his country to the artist. Arrenye officially opened Moss’s first retrospective at the Araluen Cultural Centre in Alice Springs in 1994. The following retrospective was in 1998. Kemarre Turner after consultation with Arrenye made the opening speech. The conversation between the two elders was overheard and translated.

“Rod’s paintings aren’t anything special. Only ordinary life. People going about business. Rod sees us as people, not just black people, but as people like he is, a white person. Just our skin is different. We are still living in sheds and he helps us, thinks properly about us.

People will think about you people at Irrkerlantye, still dancing and doing anthepe ceremonies. Town mob learn this from looking at the paintings.That’s why you take Rod to watch. They might believe that these things are are not continuing. But they are at Whitegate. Not just like bush communities. Community mob take photos at anthepe, the dances women do at initiation ceremonies. But we’ve got Rod with the picture in his head.

Young people will see that their culture is still alive in the paintings, showing other people how people live at Whitegate, not houses like at Charles Creek. We are the forgiveness people. White Australians will see from the paintings that the Aboriginal people still live in humpies and from soakages, and hunting on foot. So whitefellas will understand from seeing the paintings.”

But in order for Moss’ paintings to carry the complexity of such information and compress its vigour there needs to be a physicality of execution and an aesthetic order, which is anything but ordinary. We must appreciate the compositional and technical devices within the work. The fact that the flesh of the aboriginal figures is rendered in graphite whilst the rest of the composition is fully painted creates a tension and threatens to disrupt the cohesion of the whole.

Yet the graphite portraits of his aboriginal subjects within these paintings are executd with a great tenderness and familiarity. These figures are empowered, they witness, direct and execute so much of the action being depicted that they hold it all together.

The silky grey tones of the graphite which are at odds with the fully painted white people is a device that speaks of the gap which exists between the two cultures, a separation which is enforced in every aspect by the rights removed from them.

As an artist schooled in the tradtions of the West, Moss is well aware of the push and pull of the picture plane: the disruption of space by the Cubists, the emotional stirring of paint by the Expressionists, the arguments of the purely abstract over the narrative are art school debates that tend to wither under the sheer force of the reality of life itself in the centre of Australia.

Moss meets this challenge, evoking the brilliant light of day through the broken brushstroke moving from sinuous gesture to the Pointillist dot, carrying the dappled colour of ground and sky, the complimentary warm and cool of sun and shadow. The careful organizing of groups within this plane opens the space up so the eye can enter and read the narrative or ask the question. The narrative is stilled, even though the action is often taking place. Figures gesture, dogs roam, yet it is all set and imbued with gravitas.

To this end Moss looks to the great painters of realism, Caravaggio, Courbet, Manet, Bruegel, Velasquez, and Goya, using compositional devices such as the placing of groups with pivotal figures as the balancing point between clearly distinguished genre types. In some cases spiritual religious emblems drift into humble scenes of grieving or elation, evoking the spiritual world made material.

The influences of the Masters are absorbed and modified rather than slavishly copied, the ironies and follies of this depicted coming together give rise to a humour and a certain Surrealistic quality.

The political and social issues of disenfranchisement that bear down on the aboriginal community put the traditions of Werstern Art and its march towards Modernism into the back seat. How does such a brief flowing of western culture deal with meeting an ancient culture whose sense of time and timelessness is not driven by immediate material success and wealth?

As Moss has opened himself up to the ‘otherness’ of aboriginal life he has witnessed the passing of many young aboriginal men, too soon to the grave. He has joined in the hunt, nursed the elderly, ferried the sick to hospital and helped in the efforts to find small means of income.

When I read Rod Moss’s masterpiece the Hard Light of Day, I marvelled at the wonderful goodness and profound humanism of the man who wrote it. Ditto when I read One Thousand Cuts. Where could such a man come from, I wonderd. Many readers who felt as I did will look eagerly for answers in Crossing the Great Divide. They won’t be surprised that Moss’s rich life confirms the ancient insight that wisdom comes only to peoplewho were neither wise nor prudent when they were young. In his early and middle years, Moss’s ferocious hunger for experince – physical, intellectual, artistic and spiritual in their many forms – was tempered by a sense of humanity that existed in himself and others that went deep even then. The idiosyncratic, gritty but sensuous realism of Moss’s paintings shows also in his prose, enlivening while disciplining its attention to the detail of events, persons and places he describes. I know of no one like him.

Raimond Gaita (Romulus My Father & The Philosopher’s Dog)

BLUE MOON BAY

The Volcanic Side of the Australian Psyche…

The deceptively calm waters of Blue Moon Bay host a gallery of flamboyantly grotesque characters. Their winding and poignant journeys always teeter on the edge of absurdity while remaining strangely moving, testament to the enormous affection with which they are drawn. There is the sexy but troubled Solange, Pope the footy coach and founder of a new religion, and Noddy Mason, taxi driver extraordinaire who is made of wood. Chief amongst the characters is the Fatman, vital to the town’s prosperity with his gluttonous appetite and mastery of turd diving and final piped farts. In fact the town itself and its inhabitants collectively are the main game. It really is a theatre of voices, with the beautiful and often hilarious drawings always the key notes. And the saving grace of music is a lovely way to end it.

Tony Lintermans(The Shed Manifesto & Weather Walks In)